Untapped Potential: License-Exempt Home-Based Child care Providers

November 29, 2023

A study was published in October 2023 by the Urban Institute to identify major gaps in the CACFP’s coverage and ability to reach children. The study specifically focused on CACFP eligibility for small home-based child care providers who are legally exempt from their state’s child care licensing requirements. The researchers focused on three states (Oregon, Illinois, and Louisiana) that allow these providers to participate in the CACFP and suggests that there is significant opportunity to reduce food insecurity and support the healthy development of children by expanding eligibility to license-exempt providers in other states.

Why It Matters

License-exempt home-based child care providers (LEHBCC) care for approximately 11.5 million children nationwide. These providers disproportionately care for many vulnerable children including infants and toddlers, children with disabilities, children from immigrant families, families who face challenges affording child care, and families working nontraditional hours. By incorporating state practices that allow these providers to participate in the CACFP, we can expand access to nutritious meals for those who may need them the most.

Understanding States that Allow LEHBCC Participation

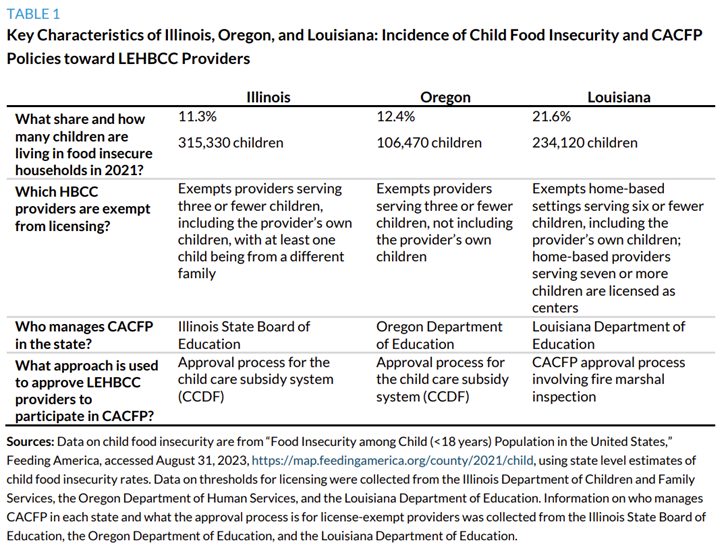

The study focused on three states: Illinois, Louisiana, and Oregon. While each state is unique, the researchers generally found more commonalities between Illinois and Oregon than with Louisiana.

What is the incidence of child food insecurity in the three states?

Both Illinois and Oregon had child food insecurity levels similar to the national average, with roughly one in eight or nine children (11.3 percent or 315,330 children in Illinois and 12.4 percent or 106,000 children in Oregon) living in households with food insecurity, respectively. In contrast, child food insecurity levels were significantly higher in Louisiana, where more than one in five children (21.6 percent or 234,120 children) were living in households with food insecurity.

Which home-based providers are exempt from licensing in our three states?

The states varied somewhat in which home-based providers were exempt from licensing:

- Illinois exempts providers serving three or fewer children, including the provider’s own children, with at least one child being from a different family.

- Oregon exempts providers serving three or fewer children, not including the provider’s own children.

- In contrast, Louisiana exempts home-based settings serving six or fewer children, including the provider’s own children. Further, unlike Illinois and Oregon, home-based providers serving seven or more children are licensed as centers.

As a result, LEHBCC providers make up a larger portion of the home-based child care sector in Louisiana than in the other two states.

Who manages CACFP in the state?

At the time of our interviews, they varied in the number of sponsors in the state—specifically, there were 10 in Illinois, 26 in Louisiana, and 3 in Oregon. (Home-based providers are not allowed—under federal rules—to participate in CACFP without a sponsor.)

Interviews suggested that the states varied in the likelihood that providers would have access to sponsors. For example, in Louisiana, providers in every parish had access to at least two sponsors, whereas in Oregon respondents said that there were gaps, particularly in the eastern part of the state, which is more rural. As a respondent in Oregon noted, “There are plenty of providers that aren’t being served because our sponsors just aren’t big enough, we don’t have enough capacity to go to other counties.”

What approach does each state use to approve LEHBCC providers to participate in CACFP?

- CCDF approval. Illinois and Oregon both relied on CCDF approval processes to determine which LEHBCC providers were eligible for CACFP. These federal requirements include trainings, annual home inspections, and comprehensive criminal background checks for all adults in the household who may come into contact with children, though states may waive some or all of these requirements for relative caregivers. In both Illinois and Oregon, the CCDF approval process was managed by the state department of human services that manages the CCDF subsidy program, which in Illinois is the Child Care Assistance Program and in Oregon is the Employment Related Day Care Program. Thus, in these states, CACFP is only available to the subset of LEHBCC providers serving families who need help paying for care and are able to get a CCDF subsidy, meet CCDF provider health and safety requirements and are approved to be paid by the subsidy program, and meet CACFP eligibility and enrollment requirements.

- Fire marshal approval. In contrast, Louisiana relies on a fire marshal inspection to approve providers for CACFP. Specifically, any LEHBCC provider who is interested in participating in CACFP has to meet a set of child care standards that the state CACFP agency established with the fire marshal’s office, which includes basic health and safety measures. This approach means that any home-based provider in the state who is caring for children in her home, whether paid or unpaid, can access CACFP if they pass the fire marshal inspection and meet CACFP eligibility and enrollment requirements.

Once a provider is approved to operate as an LEHBCC provider in each state, they can begin the process of onboarding onto CACFP, which includes signing an agreement between the sponsor and the provider, completing training sessions, and the sponsor conducting an inspection. Once approved for the program, a provider can begin reporting meals served, documenting menus, and submitting requests for meal reimbursements through the sponsor.\

Key Findings

States are not using the flexibility in CACFP to make license-exempt providers eligible.

Specifically, the relatively few states that allow these providers to access CACFP most commonly limit eligibility to providers who are approved by the child care subsidy system, which though significantly better than not allowing providers to be eligible at all, significantly restricts the eligible pool of providers. However, although it has received little attention, CACFP allows states to set up alternative approaches that would make the program much more broadly available to providers and potentially stabilize enrollment. Both Louisiana and California have developed alternative approaches that significantly expand the pool of providers who could become eligible.

The CACFP administrative and funding approach does not adequately support sponsors to enroll and support LEHBCC providers in general and is particularly inadequate to support participation of providers in underserved communities.

Our review highlighted that making LEHBCC providers eligible is the first step but will not likely be sufficient to significantly improve participation unless additional resources and supports are made available to CACFP sponsors. This is because these providers include people who are less accustomed or equipped to meet government requirements and thus need more support, and because CACFP sponsor agencies that support providers may not have sufficient administrative funding, training, or tailored materials to engage in these extra activities. These challenges are even greater for providers who face extra barriers such as language, literacy, and technology, or who have had negative experiences with government agencies.

CACFP’s policies and payment levels create significant barriers to participation overall and particularly for LEHBCC providers.

The study highlighted a number of CACFP policies and practices that can make it challenging for smaller home-based providers to participate. These include low payment rates for meals, extensive paperwork and reporting requirements, and unannounced monitoring visits.

Steps to Improve LEHBCC Provider Participation in CACFP

- States should use the flexibility in CACFP to prioritize making more LEHBCC providers eligible for participation in the program, using strategies other than limiting eligibility to providers approved for the child care subsidy program.

- Federal and state governments, and philanthropy, could provide sponsors financial supports and other resources to reduce the costs associated with recruiting, enrolling, and retaining LEHBCC providers, and help sponsors develop intentional efforts to support outreach to and enrollment of providers in underserved communities.

- Federal and state governments, and sponsor agencies, could assess CACFP policies and practices in light of LEHBCC providers’ realities and capabilities, and work to either change these policies (at the federal level) or identify ways to help agencies reduce the barriers (at the state and local levels).

For more information, read the full study: Untapped Potential: License-Exempt Home-Based Child Care Providers and the Child and Adult Care Food Program. The study was written by Gina Adams, Catherine Kuhns, and Fernando Hernandez-Lepe with the Urban institute.